Six common characteristics of a crisis

-

Sist oppdatert

24. mars 2025

-

Kategori

Persistent crises often spark cascading events, fuel crisis fatigue and drive shifts in attitudes, policies, alliances, and everyday practices

SCIENCE NEWS FROM KRISTIANIA: Crisis communication

Key takeaways:

-

Not all crises come and go quickly. Some, like Covid-19, persist over time and require a completely different approach.

-

These prolonged crises gradually wear people down, reshape society, and don’t follow the usual patterns of short-term emergencies.

-

According to Diers-Lawson and Omondi, clear and fact-based communication is essential for keeping the public informed and motivated, while fear-based messaging can backfire.

-

In long-term crises, organisations are more often blamed for how they respond than for the original cause of the crisis.

(The summary was created by AI and quality assured by the editors).

We all know what a crisis is, right? Something that happens quite suddenly and often without much warning. This thinking is in line with most academic research that defines crises as events.

They might be untimely and range in their severity from low to high, but they are typically assumed to be punctuated events that can be described in a well-structured crisis lifecycle.

The conceptualisation of crises as reflecting isolated periods of time has been problematised for more than a decade

This lifecycle includes pre-crisis opportunities for risk management, a trigger that causes the event, the short-term crisis event itself, and then the longer road to recovery and renewal.

Certainly, this is exactly what a crisis is…except when it is not.

Similarities and distinctiveness

There are many crises that do not fit neatly into this lifecycle, like the climate crisis, Covid-19, or ongoing conflicts. In fact, these ‘other’ crises have been called more names than Kanye West: disasters, wicked problems, super wicked problems, societal-level crises, novel crises, or ongoing crises.

When we think beyond the single event, we begin to realise that complex, longer-term crises are not new occurrences. In fact, the typical conceptualisation of crises as reflecting ‘isolated periods of time’ has been problematised for more than a decade.

While these prolonged crises may have many of the properties commonly associated with crises, we assert that they are distinctive, meaning that we cannot think, act, or respond in the same way. Therefore, it is important to:

1. Define prolonged crises as a novel type of crisis or hazard

2. Compare events to prolonged crises

Ripples, waves, and riptides as crisis metaphors

So, how should we describe these bigger, more challenging, and certainly more complex crises? What are their core characteristics?

Let us start with a shameless metaphor. When a bird swims across what looks to be a calm sea, it is unclear what lies beneath – whether the ripples in the water are caused by a bit of wind, a strong current, or a shark about to attack from below – because water can be deceptive to look at.

More effective organisations prepare for these ripples, assuming that it might be more than the wind.

There is uncertainty with the ripple – or the risks that practitioners have to manage. But generally, many practitioners are used to managing the day-to-day reputational crises connected to social media rumors, complaints, and the like.

Durable or persistent crises create risk or harm at the societal level

The wave, however, is clearly understood – the bigger the wave, the bigger and more powerful the break. Thinking of a wave as an event-driven crisis, there is a clear starting point.

Practitioners and academics in the field of risk and crisis communication are used to looking for the signs of major crises or tsunami-sized ones caused by major transgressions or organisational events by using risk management or issues management approaches to manage the risks.

Although the fields of risk and crisis communication/management clearly conceptualise the ‘wave’ of crisis, one thing made clear by the Covid-19 pandemic is the lack of conceptual development surrounding prolonged crises.

There is an insufficient understanding of the riptide – where the water may look calm, but when people venture into it, the strength of the tide can threaten their lives. One of the features distinguishing ripples, waves, and riptides is their durable nature. Ripples and waves are temporary, no matter the size of their effects. Riptides tend to be persistent.

Riptide of crises:

- Durable or persistent crises creating risk or harm at the societal level.

- They can emerge across multiple geographic locations.

- Contribute to or trigger multiple event crises.

- Coincide with ‘infodemics’ related to the issue.

- (Inevitably) produce crisis fatigue.

- Lead to a variety of changes to attitudes, policy, strategic alliances, social, work-related practices, institutions.

Most of the blame is likely to be assigned not to the cause of the crisis but to the response. However, blame attributed to the cause will most likely be based on politicalisation and mitigating responsibility (e.g., scapegoating others).

While beach development often steers people towards the risk, more effective beach management can reduce the risk. The riptide is a strong metaphor for the prolonged crisis because prolonged crises are not temporary abnormalities, they are not episodic, and they cannot be defined as a passing moment of chaos. But the risk they pose can be managed.

Read more:

Comparing event crises to prolonged crises

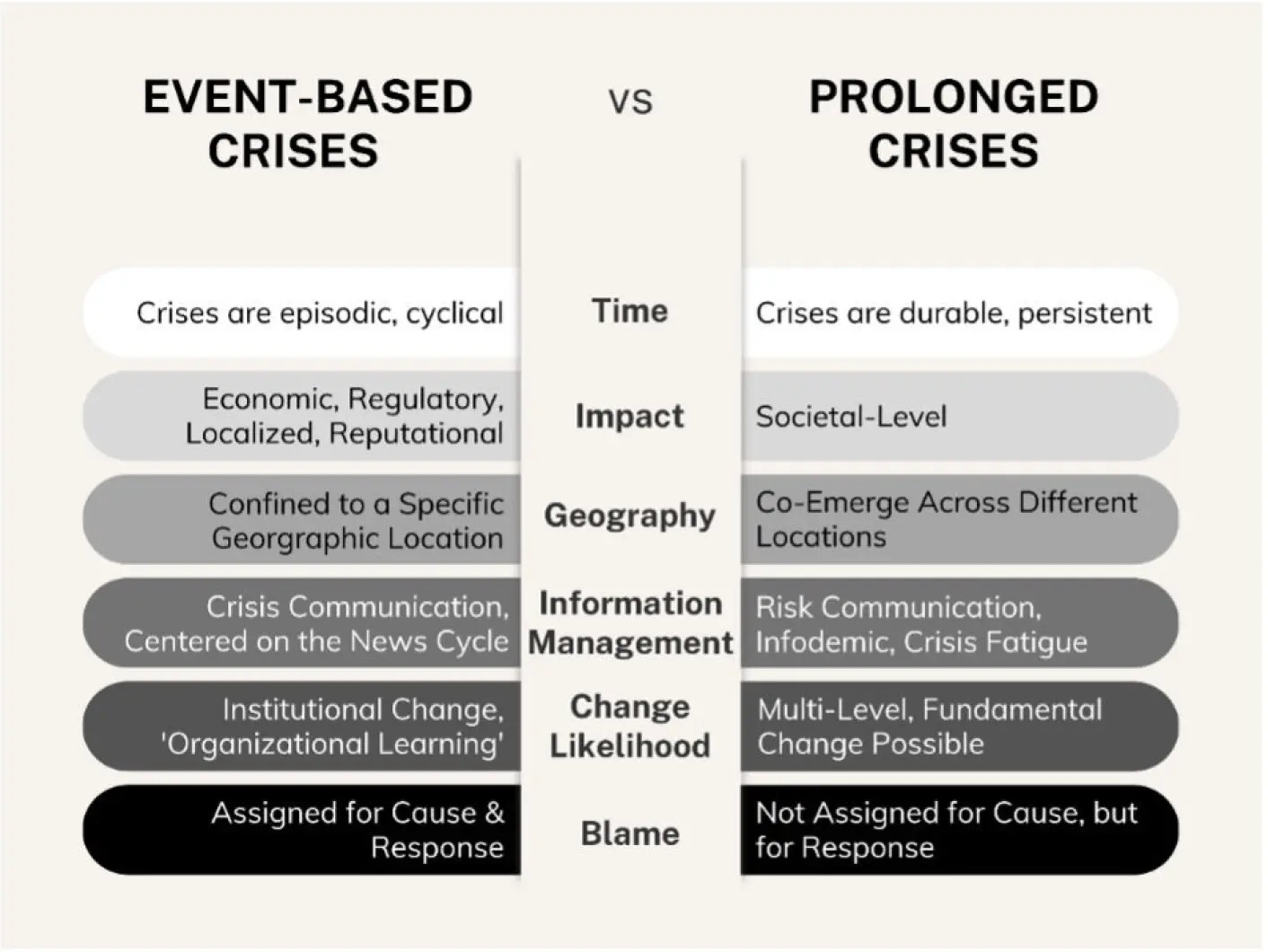

Most crises can be described based on six characteristics:

- Time

- Impact

- Geography

- Information management

- Change likelihood

- Blame attribution

While all crises will have similar central concerns and questions, the nature of those questions will change depending on crisis type. In focusing on these six crisis characteristics, we can see some of the clear differences between event crises and prolonged crises (see figure below).

Read more:

Fact-based versus fear-based messages

Effective information management is important during all crises. During prolonged crises, it is essential that governments and other organisations successfully disseminate fact-based and relevant information. That way they can mitigate the risks as much as possible and ensure support or compliance with recommendations and rules.

Infodemics are caused by both a public misunderstanding of science as well as a contested space of information. During prolonged crises, bad-will actors also use highly emotional messaging – especially fear-based messaging – to mislead citizens about issues and policies.

An event can mobilise action because fear is still manageable. In a prolonged crisis, the fear can become debilitating. Institutions that use fear-based messaging to respond to a prolonged crisis are likely to demotivate people from enacting self-protective behaviours.

What organisations are blamed for in prolonged crises

The question of blame in the context of a prolonged crisis is different from most event-based crises because the question of ‘who is to blame’ for the crisis is simply less relevant. This makes questions of blame potential more like disaster events.

Blame considerations in prolonged crises center on the (in)effectiveness and (in)action of organisational response rather than on the cause of the event crisis. More importantly, organisations – especially governments – are more likely to be viewed harshly for failing to take action to mitigate the impact either through poor preparation or poor response.

Read more:

The new normal with prolonged crises

Shifting our thinking about the role of fear is only the tip of the iceberg. It is well recognised that in the wake of event crises, organisations must often change to reduce risk, to avoid making the same mistake again, or even to build its crisis capacity.

During and after prolonged crises, this may still be true, but the nature of prolonged crises means that there is likely a new status quo – a new normal.

For example, post-Covid, the ways that many can and do prefer to work have changed. As workplaces tried to return to ‘normal,’ many found it difficult to get people back to pre-pandemic expectations.

Why?

Because prolonged crises are often associated with fundamental changes to work and consumer behaviour routines across individual, organisational, and societal levels.

Steering with the wheel instead of reinventing it

In the last of the shameless nautical puns, our argument is not that risk and crisis communication needs to start over when it comes to prolonged crises. In its brief history, research in risk and crisis communication has resulted in scores of different types of frameworks being developed and applied.

We suggest there is no point in beginning from scratch with theory development and application in the field. We should be thinking of more innovative ways of applying theory to practice and experience.

A contingency approach that focuses on a diagnostic approach to identify the factors most affecting a situation and design response strategy around those factors, might be a more agile and practitioner-friendly approach than relying on new and different frameworks.

The most important guidance suggests that prolonged crises are daunting because of the increasing global interconnectedness of people via travel, media, economic systems, food/agriculture infrastructure, and access to information. This all means that the communication and engagement realities surrounding prolonged crises, like the Covid-19 pandemic, were unprecedented.

Many mistakes were made. However, because of the pandemic, we are better equipped to understand that communication must be prioritised alongside the material crisis response (e.g., medical, emergency response, and/or policy making).

Having the best policy or medical interventions simply do not matter if people do not know about them or are unwilling to follow that guidance.

The real question is whether there is sufficient social, cultural, economic, and political will to better prepare for and respond to prolonged crises. That remains the biggest challenge.

Reference:

Diers-Lawson, A., & Omondi, G. (2024 – in press). Ripples, waves, and riptides: Reconceptualizing wicked, novel, and ongoing crises as prolonged crises. In B. Liu and A. Mehta (Eds.), Handbook of Risk, Crisis, and Disaster Communication. Routledge.

Text: Audra Diers-Lawson, professor at School of Communication, Leadership and Organization, Kristiania University of Applied Sciences, and Grace Omondo, research fellow at School of Communication, Leadership and Organization, Kristiania University of Applied Sciences.

This text was first published on forskning.no on the 13th of March 2025 with the title "Most crises can be described based on these six characteristics".

We love hearing from you!

Send your comments regarding this article by e-mail to kunnskap@kristiania.no.

Siste nytt fra Kunnskap Kristiania

Kunnskap KristianiaLes mer

Kunnskap KristianiaLes merSlik kan Vesten frigjøre seg fra autoritære og korrupte stater

Den geografiske konsentrasjonen av kritiske mineraler skaper strategiske utfordringer for Vesten. Kunnskap KristianiaLes mer

Kunnskap KristianiaLes merSix common characteristics of a crisis

Differences and similarities between event-based and prolonged crises. Kunnskap KristianiaLes mer

Kunnskap KristianiaLes merCan we leave fact checking to AI?

Companies are trying to convince us to use AI-based solutions for fact-checking. We found that human involvement remains immutable. Kunnskap KristianiaLes mer

Kunnskap KristianiaLes merHvorfor tollkrig nå , og hvem vinner ?

Tidligere handelskriger har fått skylden for Den store depresjonen på 1930-tallet. Er vi på vei dit igjen?